Although I missed a few aspects of the earliest days of computing (like punch cards and mainframes), I had a front row seat of the home computer wars that began in the late 1970s and continued for many years to come. Because I got into computers at such an early age, it’s easy for me to throw out old-timer stories about paying exorbitant prices for minuscule hard drives or talk about the age of online computing before the World Wide Web, but what I really get a kick out of is talking to people or reading about the days of computers that predate my own.

Alfred Lewis’ “The New World of Computers,” written in 1965, is such a book.

Of course today, computers are involved in essentially every part of our lives. Most of us work with them or use them in some fashion every day. In the beginning of Lewis’ book, he talks about how computers are being used to change the way things are done. One example he gives is that computers are being used to count ballots in national elections. “In the recent presidential election, the final vote was not known until days after the election.” There are a couple other examples of computers running an oil refinery and being used in the space program. Later in the book, Lewis explains to us what computers do. “Computers are used for two general purposes: data processing and process control.”

Here are a couple of other great quotes from this book.

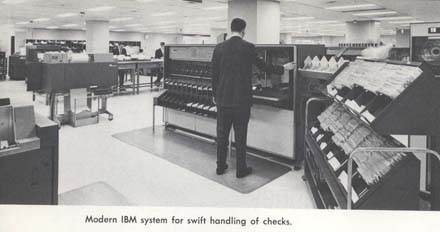

In appearance, they look more like rows of metal cabinets or lockers. Inside the metal walls, however, are hundreds of wires and vacuum tubes and transistors, as in many radios and TV sets, only much more complicated. Often they are not a single machine, but a system of several machines. Some of the largest of these systems can take up most of the space in a room larger than a school library. Other computers are no bigger than a typewriter and a desk.

One of the newest uses for data processing systems is in printing telephone books. The Montreal Telephone Company, among others, now stores its entire listing of names and addresses ina computer. When a telephone customer moves, the new name or changed address is merely fed into the machine. The change is automatically inserted into the right place. In years past, clerks had to spend hour after hour in changing cards that were used in preparing the directory. Now the list is always up to date in the storage files of a computer. With the aid of a printing attachment, the computer can print a master copy of the list at the rate of 500 lines a minute. This master copy is photographed, and thousands of duplicate copies are made.

A computer consists of four main parts. It must has a means of getting informtion into it; that is, an input. Tables of figures and other information must be stored, and this storage is done in a memory. A processing section is required for doing the arithmetic and other operations. Finally, it has to have an output to make the results of its operations available.

What I really like about that quote is that it doesn’t mention keyboards for input, or monitors for output. This book predates both of those things we take for granted. Lewis continues.

Input for a computer normally is not in the form of typed or handwritten words. More often it consists of holes punched in cards or paper tape. These holes are sensed by a ray of light or by tiny metal brushes. Bother of these convert the holes into a code of electrical impulses. The output of a computer takes comewhat the same forms as the input. The result may be information on punched cards, punched tape or magnetic tape, which in turn will be handled by other machines. The output also may be typed out on an automatic typewriter.

There are a lot of other great historical comments in this book as well. It uses the term “data-phone” instead of modem, and predicts handwriting recognition, but skips keyboards.

In the last chapter of the book we are told that computers will lead to new jobs for programmers, engineers and mathematicians, “but not mechanics as machines will be able to lubricate and fix themselves. We will also need a lot of social workers and government planners to help men and women adjust their behavior to the world of machines.” The biggest problem we will face in the future is “solving the problems of unemployment, education, and training of people for new types of work” that computes will bring.

Of course, it could not predict that even garages will use computers, if only for their billing and inventory systems.

Seems laughable now, but what a breakthrough back then. This inspired me. I’m going to go back and read “1984” to see what was considered ‘futuristic’ when it was written that is now commonplace and accepted. And, what’s a typewriter?

“Some new computers are no bigger than a typewriter and a desk.”

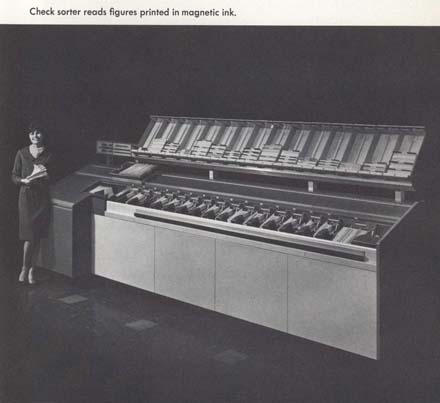

That pic is SO going on my cubicle wall at work!