The first My Life with the Thrill Kill Kult (TKK) album I ever owned was 1989’s Kooler Than Jesus. Life before the internet was different; back then we discovered new music through MTV, magazines, radio, friends, and occasionally, live shows. When I was sixteen I’d cash my paychecks and drive directly to Rainbow Records of Midnight Music, where I would browse the heavy metal section and buy new cassettes based solely on how offensive the song titles or album covers were. A few years later at Pizza Hut, a middle-aged coworker of ours became so concerned that my friends and I were on the highway to hell that she bought a copy of television evangelist Bob Larson’s Book of Rock and passed it around to each of us, urging us to learn about the satanic and occult messages hidden in modern rock. Not only did I steal the book (I still have it), but I used its list of featured bands as a shopping checklist. The entry for My Life with the Thrill Kult Kult refers to them as a group of offensive heretics who sing about sex, drugs, and Satan. On my very next payday, I went out and bought the album.

While samples have always been a part of dance music, Kooler Than Jesus relies on them heavily, sometimes as the only voices in a song. Many of the samples come from movies — but again, before the internet, there was no way to know what movies they were from unless you just knew. I remember nearly jumping out of my chair while watching Amityville 3D and hearing the line “reality is the only world in the English language that should always be used in quotes,” recognizing it immediately from the TKK song “Nervous Xians.”

There was, though, a series of somewhat haunting samples featured on the album. They sound like a woman being interviewed. The voice is breathy, almost raspy, and although different phrases/samples are featured in multiple songs, it’s obviously the same woman. In one sample she says “I live for drugs, it’s great.” In another, she says somewhat rapidly, “and everybody thinks I’m high and I am.”

Today, all the samples used on this album (and every album, ever) have been identified. The high woman who lived for drugs was named Marcy, and her story is a fascinating one.

Marcy was born and grew up in Flint, Michigan. The subject of an unhappy home, Marcy joined the hippy movement and hitchhiked around the country, ending up in New York City. While there, a journalist writing for Newsweek named Bruce Porter was looking for a story. Bruce and Marcy crossed paths in 1967, and the result was an interview that would spark a series of events that would change her life forever.

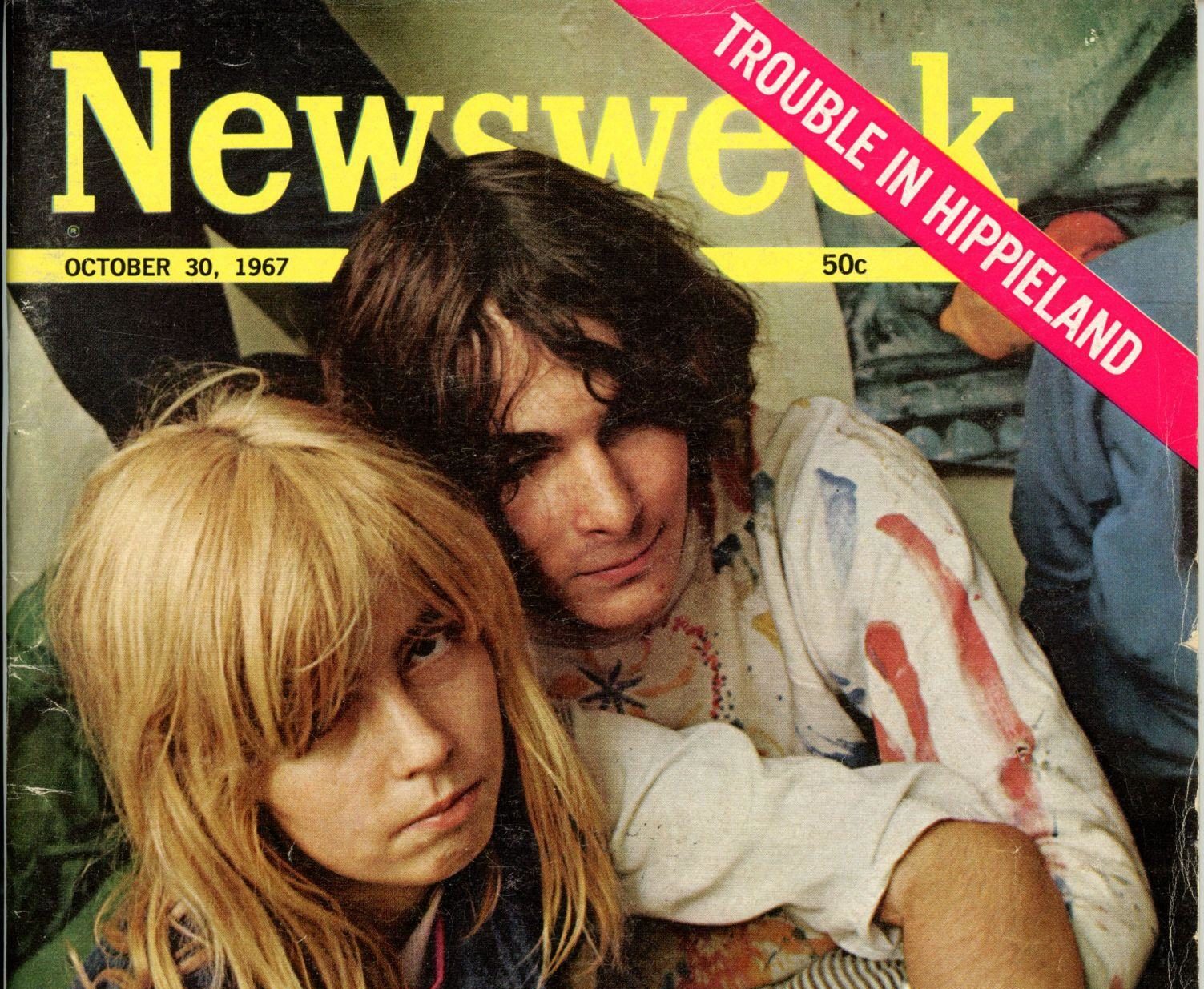

Porter interviewed Marcy about her past and life on the streets on the condition that he would not mention her name. Then, in the article, he mentioned not only her name, but her hometown of Flint. Newsweek ran a picture of two homeless kids on the cover under with the banner “TROUBLE IN HIPPIELAND.” The article was titled “Gentle Marcy: A Shattering Tale,” and in the article Porter somehow managed to get multiple facts wrong. He said she had been hit with a milk crate, beaten up in a park, and paid $200 to get an illegal abortion. Marcy later denied she said any of these things. There’s no audio recording of the interview so many of the claims boil down to “he said/she said,” but Porter does specifically mention that Marcy was 17 years old and a runaway when in reality she was 19, making her a legal adult.

Link: Gentle Marcy: A Shattering Tale

Marcy and Porter went their separate ways and if Porter had kept his promise not to use Marcy’s name in his article, that would have been the end of things. But he didn’t (keep his word, that is.) A week after the Newsweek article was published, Steve Young, reporter for New York radio station WNEW, went downtown and tracked down Marcy. He offered her and a few of her friends to stay in his apartment overnight. While they were there, Young also interviewed her. Again, the details are sketchy — Marcy says she didn’t know she was being interviewed, much less recorded, but Young said it was clear she was. Audio experts point to the fact that reel-to-reel recorders WNEW reporters had access to were slightly larger than a briefcase, and Marcy’s voice sounds like she is speaking directly into a microphone and doesn’t wander off the way a person might if being secretly recorded.

Young’s interview was even more personal than Porter’s from Newsweek. After going into her personal history and pulling out details of her sex life and drug usage, Young offered to let Marcy use his phone to call her parents back home in Flint. The conversation would pull at anyone’s heartstrings as Marcy begs her mother to “please still love me after you read the Newsweek article” and says she’s worried her parents don’t love her anymore. The other side of the conversation was not recorded, but through Marcy’s responses we can tell what was being said. Her parents repeatedly offer to send her money if she’ll come home. At one point in the conversation, Marcy sniffles and responds, “no, I’m not lost.”

Whether or not Marcy agreed to be interviewed by Young or knew she was being recorded is historically irrelevant. Young took the interview, packaged it up, and broadcast it on both WNEW-AM and WNEW-FM. The interview gained so much publicity that the interview was pressed onto vinyl and sold as a record. The entire interview, which is about 25 minutes long, can be heard at the following link. There’s an edited version available on YouTube that omits the phone call. Listeners were so moved by the interview that they mailed more than $5,000 in cash to the station in hopes of getting it to her. (Marcy never got the money, and the radio station “doesn’t know where it ended up.”)

Article: Full recording on Crooks and Liars

Here is the slightly abbreviated version, on YouTube:

Nobody knew where Marcy went after that. In the two interviews she talks about going to Missouri to work on a farm, on buying a bus and driving it to the Grand Canyon, and opening up a daycare, among other things. According to Young, she and her friends were headed to San Francisco.

If you thought this story was over, it’s just beginning.

Bruce Porter, the man who interviewed Marcy for Newsweek, was hired as a professor at Columbia University. He taught (of all things) Journalism Ethics, despite the fact that his biggest story involved using a girl’s name when he had promised not to. Some 40+ years later, Bruce Porter decided to track down Marcy and “apologize to her.” (There’s a reason that’s in quotes.)

Porter and his colleague Dan Loewenthal flew to Flint, Michigan in 2011 in an attempt to find Marcy — again, ostensibly to apologize to her. Porter’s motivation becomes questionable when one learns Dan Loewenthal was also a documentary filmmaker, and the pair’s alternative goal of creating a film about finding Marcy is exposed. To apologize for exposing Marcy’s name, Porter reaches out to the local Flint newspaper prior to his arrival and the result is an article that runs on the front page, again with Marcy’s name. Porter and Loewenthal hole up in the local library and pored through old yearbooks, looking for clues. Depending on which version of the story you believe, Porter says a mysterious biker known only as “Moon” entered the library, told Porter Marcy’s last name, and immediately left the library. The librarian also claims to have discovered Marcy’s last name, a much more likely scenario in my opinion.

Armed with Marcy’s last name, Porter and Loewenthal were able to locate Marcy’s parents’ home and arrived at the front door with cameras recording. According to Porter they didn’t expect to find Marcy at the home (he claims he thought she was in Hawaii — another fib he got caught telling), but she did. According to Porter, Marcy was pissed (and rightfully so) about the Newsweek article, but she literally had no idea about the WNEW interview (or record) that had also been released in 1967. It was during this meeting that Marcy also became aware that that snippets (samples) of the record had appeared in several industrial dance songs. As you might imagine, Marcy was less than thrilled to learn that.

She never got paid for those, either.

While visiting her inside her home, Porter “forgot to mention” that an article would be appearing on the front cover of the Flint newspaper, sparking interest in her story all over again. A few weeks later, he forgot to tell Marcy that he’d written another article about her titled “Lost and Found,” in which he details his search for her. In a story in which he says he tracked down Marcy in an attempt to apologize for using her name and violating her privacy, Porter managed to this time include her last name, the town she lives in, and a picture of her house with the address numbers plainly visible. I was able to track down the address and view Marcy’s house on Google Maps in about 2 minutes. The Flint newspaper ended up running five front page articles about the situation which traumatized Marcy all over again, especially as links resurfaced to both the original interview and the audio recording of her from 1967.

Article: Lost and Found

In the last line of the article Porter says “It was as if I’d never learned a thing. Oh, Marcy, I thought, I’ve done it to you all over again!”

What a jerk.

For some time after their initial meeting, Loewenthal continued to contact Marcy in an attempt to convince her to sign a contract to appear in a documentary about the meeting between her and Porter. (They agreed to pay her $500.) During this same time, Porter repeated many known lies and falsehoods about Marcy to the Flint reporter which made it appear that Marcy was lying about her past and whereabouts. Porter and Loewenthal got Marcy to sign a contract releasing the footage they had shot, but when she demanded final cut of the documentary, it appears the project was abandoned.

It’s tough to sue someone for an article that was written 50+ years ago, especially without clear documentation from either side. (Young, the radio journalist that interviewed Marcy, passed away years ago.) But when Porter began publishing his new articles that recycled facts Marcy said were false, she sued the Columbia Journal for libel and defamation of character. Although I was able to find many articles mentioning the lawsuit, I was unable to find the results of it.

Article: Woman Sues Columbia Journal

If you listened to the WNEW interview above on YouTube, you’ll recognize large portions of that interview in the first 90 seconds of Meat Beat Manifesto’s “Acid Again.” Again, Marcy was never compensated for these samples, which (according to her) were recorded without her permission in the late 1960s.

And finally, here’s are the two TKK songs that stared my curiosity into all of this.

Marcy’s voice is unmistakable. It’s a sample I knew by heart, but never knew the heart behind it.

According to iMeadiaEthics, “Marcy is known as a community volunteer according to members of the Flint Library staff. Working with neighbors and school children, she created a free community garden. She taught canning with Flint librarian Juliet Minard and taught other free courses in jewelry-making and gardening. This is how she wants to be known.”

Fascinating story, I never knew where that sample was from. Have you seen the documentary Industrial Accident? It’s about Wax Trax Records and the bands that were on the label. If your a fan of Thrill Kill, Ministry, or KMFDM it’s definitively worth a watch.