“You are definitely the most interesting person I’ve seen all day.”

A fun phrase to hear in some situations, an eye exam at the Dean McGee Eye Institute not being one of them. After three hours of tests, scans, and evaluations, the optometrist weakly smiled at me and said, “I wish I had better news for you.”

I wish he did, too.

First, he told me I had Horner’s Syndrome. I already knew that, and it’s not a big deal. Horner’s Syndrome is caused by damage to a group of nerves and has a few major symptoms. The dead giveaway is two different colored eyes, followed by (and I’m quoting Wikipedia here) “miosis (a constricted pupil), ptosis (a weak, droopy eyelid), apparent enophthalmus (inset eyeball), plus/minus anhidrosis (decreased sweating).” I don’t think my eyeball is inset, but I do have all the other symptoms: in regards to my green eye, the pupil is constricted and slow reacting, the eyelid slightly droops, and I do not sweat on that side of my head. While some people develop Horner’s Syndrome over time, most people (like me) were simply born with it.

The bigger concern was the results of my eye exam.

Let’s start off with my vision test. In my green eye (the “bad” one), the results of my eye exam were 20/1500. That means that, at least in that eye, objects that are 20 feet away look like they are 1,500 feet away for me. This became pretty clear when, with my good eye covered, I could not read a single letter on an electronic eye chart 8′ away. The eye charts they use are presented on a 24″ monitor, and they will continue to enlarge the letters until one single letter fills the entire 24″ monitor. With my left eye, I can’t read a letter that fills a 24″ monitor from 8′ away.

I had heard of macular degeneration before. Just two weeks ago, Roseanne Barr announced she was going blind from macular degeneration. In my green eye — again, the bad one — I have what’s called macular atrophy.

Here’s a quick eyeball lesson. I didn’t know any of this before yesterday so my apologies if I get any terminology wrong. In the back of your eyeball there’s an area called the macula. Across the macula are tiny bands that allow your retina to focus on things. This is all about your “straight ahead” vision, not peripheral vision. The most common type of Macular Degeneration (dry) is the wearing down of those bands over time. Vision loss is gradual with dry macular degeneration. 90% of the people who have macular degeneration have this type.

Atrophy, unfortunately, is worse. If “degeneration” is the journey, “atrophy” is the final destination. My bands done degenerated. There is no fixing this eye. Even what we call an eye transplant (which is really just a cornea transplant) would not fix this. The good news is, it can’t get any worse in that eye — which is akin to saying, “at least that dog turd can’t get any stinkier.”

Now let’s talk about what I used to call “my good eye,” which I must now call “the better eye.”

In my better eye I am showing signs of Macular Degeneration, which apparently runs in my dad’s side of the family. The doctor said the macula bands in my good eye have already started to degenerate. Usually he only sees this amount of degeneration in his older patients, but… lucky me. There’s no way to repair those degenerated bands. The only “treatment” is to slow down the degeneration.

My doctor referred me to a list of things one can do to slow down macular degeneration. I have personally grouped them into three logical categories.

– Don’t smoke, lose weight, lower your blood pressure: eyeballs require large amounts of oxygen and blood to function. Anything that restricts the flow of oxygen or blood to the eye contributes to macular degeneration.

– Exercise regularly: Again, increasing the flow of oxygen in the bloodstream helps.

– Diet and supplements: Eat a nutritious diet that includes green leafy vegetables, yellow and orange fruit, fish, and whole grains. Take supplements. Wear sunglasses and hats outdoors.

Based on that:

– I don’t smoke, but I do need to lose weight and lower my blood pressure. That just turned into a priority. Exercising regularly is a part of that.

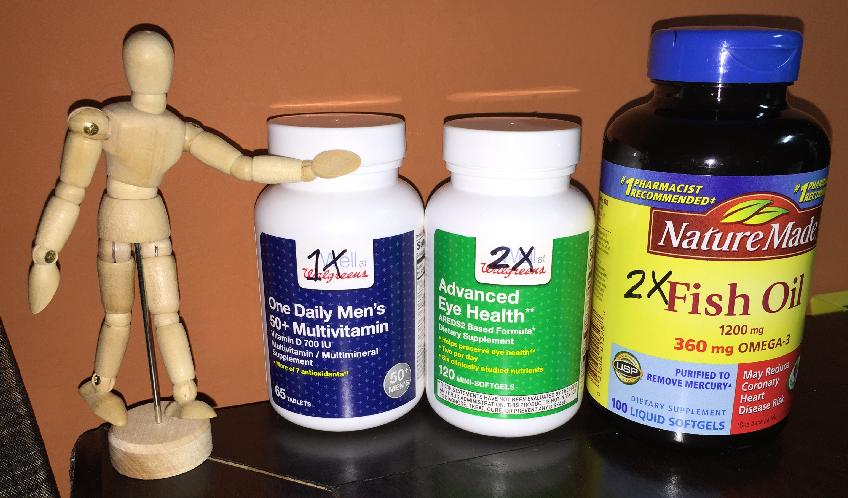

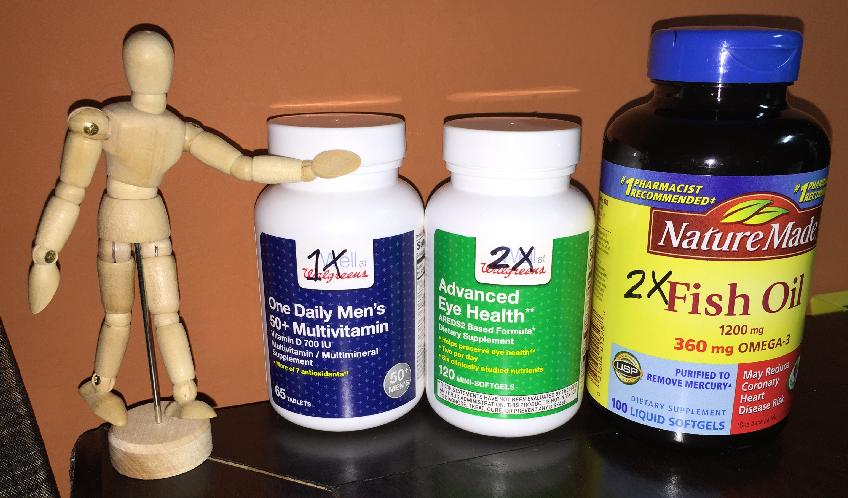

– I see diet changes in my future. And just in case you don’t think this is serious, Susan brought home my new breakfast regimen last night:

Short of stem cell therapy, exercise, vitamins, and wearing sunglasses are about all I can currently do. (Smoking pot with Roseanne Barr is not an option.) While vitamins and all those other things won’t restore any vision I’ve already lost, it will (can) help me retain what I currently have — which, again, has suddenly become a pretty big priority.

I am sharing all of this not because I am looking for sympathy or prayers or well wishes from anyone but because I am a journalist at heart and have a need to document things around me, good and bad. While my macular degeneration should hopefully be gradual enough that I’m not continually documenting any increases in vision loss, if there’s a major change I’ll definitely provide an update. Other than my own new personal health goals, it’s back to business as usual.